( Alternative title;) A Mountaintop Food Review By Eric Wartenweiler Smith

Ascent Day 1

Licancabur Volcano, Bolivia

0500; Breakfast at the Refuge; Fresh bread rolls, jam and honey we brought from Antofogasta, powdered milk,” Hapi”. and Mate de Coca.

At 0530, I am informed by team logistician Christian Tambley that I appear out of my element, and my capacity to adapt to and survive in these environmental conditions is in question.

Christian is a very experienced extreme altitude mountaineer. He is wise, honest, and totally unsympathetic to my attempts to get used to life on the Altiplano. His view of our toils is measured from the geological perspective. ‘The scientific equipment for the entire expedition did not arrive? All life on earth is about to be eliminated by the inevitable impact of a meteor, and you are worried about some mislaid equipment. Stop weeping.”

Buddha meets Jack-ass....

Rob brought some coffee from home; just enough to get himself through the expedition, watching and smelling him prepare it with hot water from Maxima’s wood burning stove is difficult. He couldn’t bring enough for everyone. We all had the chance to bring some sort of ”comfort food” with us. Some chose more wisely than others.

Rob works in the Artificial Intelligence end of robotics, teaching machines to understand what they are seeing, and in his free time has climbed many mountains, like Half Dome in Yosemite. He understands the importance of good coffee for a mountaineer.

I understand the value of good coffee too. I am a sailor and diver from Key West Florida. I grew up on café con leche. I teethed on Baby’s Breakfast roast. And as my experience with high altitude climbing is limited to climbing in and out of ancient liberation trucks in Tibet 21 years ago, I am now acutely aware that coffee is just one of the important things that I have not brought with me on this expedition.

After final medical checks, the team climbs into the already loaded vehicles and travel as high up as they can make it, and begin the ascent toward Mid Camp;

By 1430 we arrive at Mid Camp; we eat cheese sandwiches on Maxima’s rollsand pitch our tents,

For weeks we have based at the Refuge; a small collection of retired stone buildings from an era of hard-scrabble mining that now serve as a rest stop for trucks and Landcruisers crossing the Altiplano from Chile to Bolivia. And

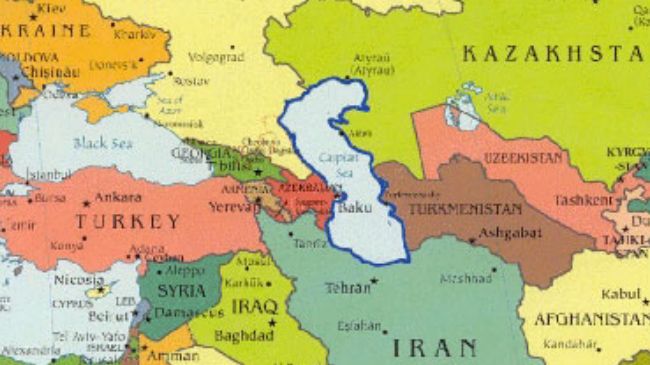

mountaineers. They come from all over the world to climb Licancabur. Not nearly the highest volcano in the Andes, nor the most difficult among the hundreds of volcanoes that make up the Andes chain, Licancabur remains one of the most famous and most compelling. It has an interesting shape and has been a destination of Incan pilgrimages for perhaps thousands of years, back to when they used it as one corner of a revered ’Triangle of Fire”.

For our group the pilgrimage is in its 5th year, and the High Priestess isDr Nathalie Cabrol, a Planetary Geologist representing the NASA Astrobiology Institute and SETI, and the reason for the journey is not the mountain itself but the tiny lake in its summit crater. It is a unique spot on earth so extreme that it is analogous to Mars, and

the critters that live in it, titled “ Extremophiles”, are surviving and thriving there. Cabrol Et Al want to study them to better know where to search for life in extreme environments off the earth. I have been invited to join the team based on my experience as a diver in using a new diving technology to explore the lake and try to understand how life got there and how it survives.

Nathalie is originally from France, and her Husband and expedition partner Edmond Grinn is Swiss. They moved to Californiato work at NASA’s Ames Research Centerbecause there was no European space agency capable of using her unique knowledge of Mars. At 25 she advised the Russian Academy of Sciences on Mars’ Gusev crater, and later at Ames her argument to land the Mars Rovers there triumphed over 25 other proposed locations. She learned perfect English and scientific English too. Unfortunately, she is not interested at all by food.

Dinner at the refuge had been consistently good, though simple. Potato soup, Chicken or Llama, Quinoa or rice, followed by tea and a slide show of whichever media person has finished editing their work

that day. Maxima is the queen of the refuge, which has a roving population of about 10 to 15. Bolivian guides,

drivers, and the occasional mountaineers. It is 2 hours drive across the desert to the next refuge, and 6 to the first real town, Uyuni. Across the border in Chile, a paved road and 6,000 feet drop in altitude leads to the

lovely oasis of San Pedro de Atacama . The Bolivians seldom have an opportunity to cross that border.

“Medio Encampamento” on Licancabur is a big switch from life at the refuge, and an instant introduction to what the next 4 days will be like. For dinner I eat Couscous A Volait, a freeze dried meal in a foil pouch that you pour hot water over. Henry (Bortman, the science writer and Photographer) shares some instant Miso Soup, and I

follow up with ramen noodles and mint tea. Caffeine is supposed to be unhelpful at Extreme Altitude, a boundary we crossed into at 5000 meters according to the International Mountain Medicine Society, so I am trying to

wean myself off.

What if we had to live this way?

We are on the eastern, Bolivian side of the mountain, and as soon as the shadow falls over our camp, which is a flat shelf constructed by removing some rocks in a miles long rockslide that has reached an un-easing equilibrium. By pulling some rocks out of the slope, and stacking them up to make a wind break. We have a flat spot just big enough for the 4 tents for 8 people. When the shadow hits we are suddenly on a cold and windy precipice, and inside a tent is the logical place to be. We use tiny gasoline stoves to heat water, I find a hollow in the rocks above the camp and sit contemplating the amount of force it would take to send the entire slope back into a fluid movement in which we

would all disappear, There was a mild earthquake the day before, and Christian says they happen several times a week here, The Andes are, after all, a fault line. Circle of Fire, you know.

I sit and watch till the sun sets an hour after it abandoned us of any radiant heat or comfort. The thin atmosphere traps only freezing wind gusts. Wearing all the expedition weight clothing that I brought, plus the sponsor’s expedition weight down jacket, hat and balaclava. It gets cold. My insulated thermos cup hasicicles where I

spilled little sips of tea trying to drink thru thebalaclava and it froze instantly. I can see the refuge down below

on the edge of the Altiplano, once harsh and alien enough, and now a memory of comfort and home.

Finally I give up contemplating geological and thermal opportunities for my own extinction, and climb into the tent with Bortman and sleep well enough.

Ascent Day 2

Breakfast at Mid Camp is not hurried.

I have 2 ramen packets and tea. Macario and the rest of the Bolivian guides arrive, with more of our

scientific equipment and diving gear. They had started carrying gear up the

mountains in stages 3 days ago. Macario will have climbed Licancabur 398

times as of today. He is 59 years old.

It’s funny how your sense of smell changes in extreme environments. When I

was a kid I read books about mountaineers and artic explorers, and

always was interested by their accounts of being able to, say, smell a

polar bear from a mile away. In the Refuge, I could smell the real

coffee in Robs cup from 30 feet, over the Nescafe of

one sitting next to me. And one day I picked up a mysterious whiff

of,bourbon?

I had also read about how a mountaineer’s teeth would turn brilliant white during the course of an

expedition, because the bacteria that live in your mouth and discolor teeth

perish at extreme altitude. I hopefully watch for signs of a ‘Hollywood

Smile”, but maybe that’s just in the Himalayas.

Summit

Camp

is a wonderful, roomy shoulder an hours climb short of

the summit rim and the entrance into the volcano’s crater. We arrive in the

afternoon and there is plenty of room for everyone’s tent. Several of the

stoves don’t work today, so we work to get one going and keep heating up pots

of water for each party. I will now be sharing a 3-person tent with Christian

and Mathieu. Henry turned back tearfully an hour up from Mid Camp, with

several symptoms of oncoming Mountain Sickness. He descended to Mid Camp with

Auralio and waited there till Pablo and Martin from the documentary film

production came up on their training climb. They helped him descend, feeling

better with every drop in altitude.

Christian and Matthieu’s tent is like a dorm room or Frat house. It’s

a mess within minutes of construction, with food stashed in every

corner and dirty socks, and they chat like birds, both speaking English well

though Christian is Chilean and Matthieu French. We don’t cook

dinner till after dark, by which time the other tents are all asleep,

and we make 3 courses out of it. A freeze dried salmon dish, some

pasta, tea and desert. All cooked on the little stove

in the vestibule of the tent, while we sit cross legged or lay across

the piles of sleeping bag and expedition clothes chirping about

geology,engineering, and travel.

After dinner I climb out to sit till its too cold to be amazed at being on

top of a volcano in a range of volcanoes that stretches across four countries

and till the earth drops away out of site. We sleep shoulder to shoulder too

tightly packed, but warm.

The next morning, granola bars are an option, but anything hot

looksbetter, so I go back to the ramen. Rob and Clay do too. We deliver

a pot of hot water to Nathalie and Edmond, and they make

breakfast soup in their tent. The sun peaks over Argentina’s shoulder and

bores into the cove summit camp occupies like it was a satellite dish, and

soon it is so warm and we strip off layers of coats and jackets and wonder

why we even had them on only an hour before.

We start our slog up to the summit and in the morning calm, and I get my first view of

the lake that caused all this trouble. It looks like an emerald cut flat

on top with thousands of facets facing down onto the wet rocks.

Soon the wind picks up and ruins the effect, but doesn’t remove it from

my memory.

We do science projects. Clay assembles the remote control boat and

makes a 3D map of the lake, and installs the UV radiation

meter. Nathalie collects surface samples of ostrocods, copepods,

cyanobacteria, diatoms and a fat little shrimp-like creature with her

plankton nets, She gets very excited because she has never seen the fat ones

before.

For lunch we have cheese and cold cut sandwiches that were

made up by Maxima the day before and carried up by the guides. They often

leave the refuge at 3 am to be at summit camp by 8, carrying a load of up

to 35 pounds. Macario is the leader, followed by his son Auralio, and

Barnabe, Martin, and Bernardo. We also have some soldiers from the

Bolivian Army helping us out. I’m not sure if they are getting paid extra,

or just looking for something to do. They might be the fittest

infantrymen around, judging by their ability to scale the

mountain so fast early in the dark, and

then literally run back down the scree field slopes to be back at their camp for supper.

Rangers from the nearby Bolivian National Park also join us at the lake to collect the samples, they

are tall and schooled, and look different than the soldiers, but still wade

into the lake that was frozen across when we woke up and collect samples

for Nathalie with bare arms and hands, sweeping the plankton nets back and

forth, My own hands become useless in just a few minutes in the water,

and I stuff them hard and stinging in my armpits and hop around till I can

try using them again.

We leave the lakeside to ascend to the rim and descend to summit camp around 1600. Along with

the samples, I collected some lake water in my

bottle. There is a shortage of drinking water and I have been thirsty for days and

my lips are cracked, but no one else is complaining.

We get back to Summit Camp and Pablo and Martin have arrived.

About the Altitude;

As an ex-paramedic, I was elected medic for the expedition, and so have

studied up on some of the maladies we might encounter, such as diving accidents and altitude sickness.

Here are some notes;

La Paz, Bolivia, is the Highest National capital in the world. The

Bolivians we meet and work with have lived a life above 13,000 feet. Macario has never been lower than

Cochibamba.

In planning to join the expedition, a friend told me of people dropping dead

upon getting off the train in La Paz, others warned ofCerebral edema, Pulmonary edema,

and other ailments that come with a sudden ascent to altitude.

The NASA Safety Review Board reviewed our expedition acclimatization

program to make sure we were not pushing upward too

aggressively. We spent 2 days at 8k feet in San Pedro de Atacama. We

took Diamox, a drug that thickens your blood and decreases ones risk

of waking up at night in a panic that you have completely stopped

breathing. We then spent 2 more relatively restful

days at the Refuge on the Altiplano at 14,000 ft before starting to do science work on the flanks

of the volcanoes themselves.

The shortness of breath we encountered of the first two stages was acceptable,

even cute. Certainly a good way to know you were going on too long with a

story when you have to pause for a full minute to catch your breath before

dropping the punch line. Wrestling your way into a sleeping bag

at night might require 3 complete breaks. Lacing up your mountain boots was

exhausting.

The International Mountain Medicine Society

describes Acute Mountain Sickness as an intense headache combined with

any one of a number of symptoms such as: Nausea, vomiting, loss of

appetite, or lightheadedness.

The IMMS does not go into detail in describing the headache.

But I will:

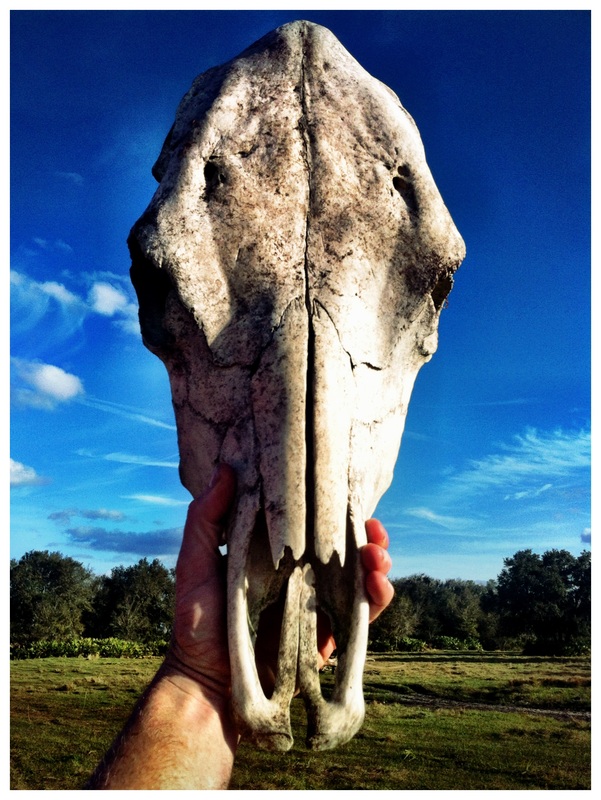

After Training Climb One, to about 18,000 ft, on the exploded volcano Juriques, I came to the

conclusion that an accurate generalized description of an altitude

headache was the effect of a larger sized medieval style axe, imbedded down the centre

of the scull, from back to front, with a subsequent twisting or

torqueing moment applied on the long handle. That is the baseline symptom. All you

need to add to push the experience over into symptoms of

dangerous and frequently deadly Acute Mountain Sickness, is a little

lightheaded-ness, or a queasy tummy.

The cure for AMS is to rapidly descend to the last place you spent the night without any

symptoms at all, including headache. For emergency treatment of someone incapacitated and

unable to descend. we have brought along a Gamow Bag, a portable rubberizedchamber that you can stick a victim of AMS in and inflate with a footpump. We tried it out in San

Pedro, me inside and Randy pumping, and believe it would work,

provided the pumper friends do not share the symptoms. They would have to

continually man the foot pump for the minimum of 2 hours while one is being

treated, hard work that makes them short of breath and at risk themselves.

Pablo and Martin did not have the luxury of a slow ascent.

They come from Buenos Aires, where they just finished shooting

a series for the Discovery Channel, spent one night in San Pedro, one

at the refuge, a training climb to Mid Camp, and the next

day a 3 am

start a 7 hour ascent strait to the Summit Camp. I could

practically see

the axe handle sticking out of the back of their heads. They

acted cool though, ate laughing cow cheese, sardines and crackers, and

shota time lapse of the sunset, I check on them for other symptoms often

enough to be a pest before they disappear

into their tent for what had to

have been a miserable night.

Dinner;

We eat freeze dried Indian Curry with Chicken. Christian

makes a desert of freeze dried Strawberries and Cream. The package itself had

been unused on a previous Everest Expedition, and was given to Christian by

a mountaineering friend. It was inedible, and I forgot to ask what

year the Everest expedition was and if they were successful despite

such lousy desserts. I tell the story of Napoleons Lost Fleet and how

I almost met my own end in the sea, and we slept alternating head to feet for more wiggle room.

Diving Day One.

Every one was up early. I tried the freeze-dried Omelet de Jambon, but it was terrible,

so had more Ramen Noodles and extra sugar in my tea. I strained out the

copepods, ostrocods, and chubby shrimp that had gotten into my water bottle

by pouring it through my balaclava as a sieve before boiling the water.

The lake is made of snow melt, and should be relatively safe, but I am

reminded that Laguna Verde down below is rich source of arsenic, and

also remember from Tibet that some

high altitude lakes have a parasitic worm that goes directly from drinking

water to your brain, where it causes seizures, coma, and death. I boil it

well done....

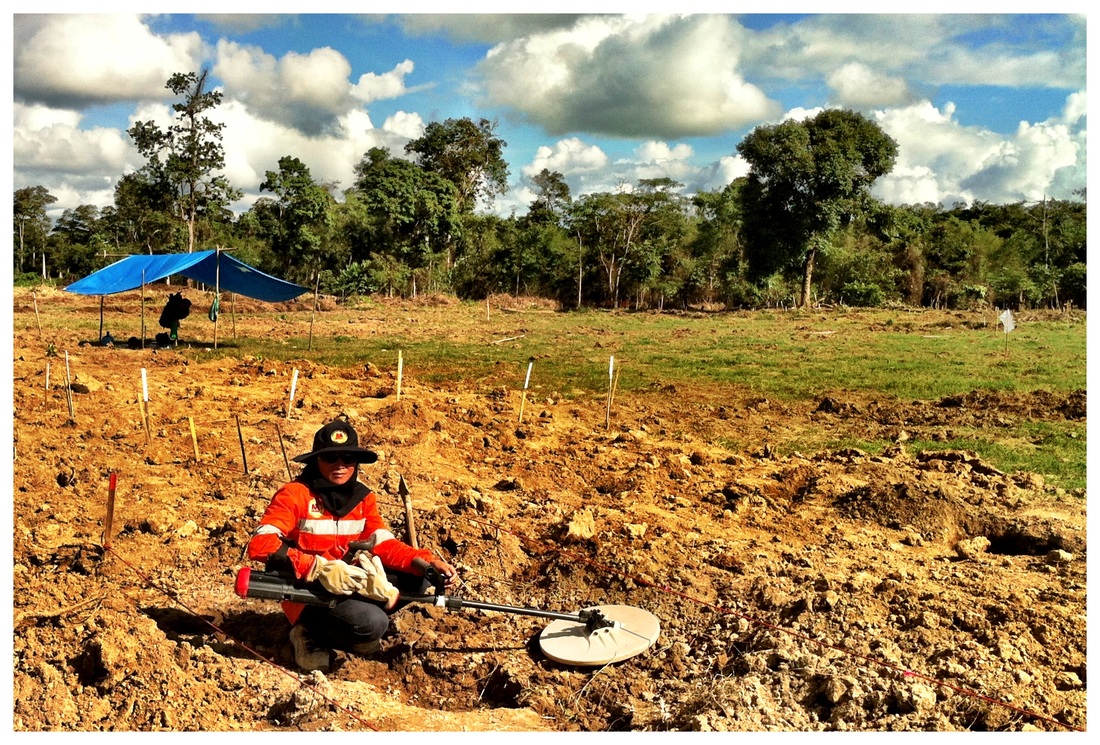

The diving goes well. Our Diving Safety Officer Randy had suddenly

removed from the ascent team by the Safety Review Board, due to a

virus in his coronary bundle branch and its subsequent ventricular arrhythmia.

He feels fine, but really frustrated at being unable to climb, and to lead the dives he had planned for months. With one diver missing from the team, we had to

rewrite the dive roster, the roles and objectives. I have to take over

Randy’s responsibilities during the diving. That means I am off the dive

roster, too.

Nathalie, Rob and Clay are all well trained for

the mission. I read out protocols and

write down times.They collect samples

and video the colonies of critters

surviving on the lake bottom. These

creatures have been isolated from the

rest of the world in a practically

Mars Like environment for who knows

how long. They are bombarded daily by

enough UV to mutate them all to

death, plus extremes of temperature and just

plain isolation makes

them unlikely to exist, but instead they are thriving,

the water is thick with them despite its clarity, swimming and fluttering

tails and antennae, dining on another eco system not so easily seen

but also abundant.

The day is beautiful and there is temptation to make a second dive.

The timing is critical. Although the day is warm in the crater, the water is very cold and

it takes the divers more than an hour to recover while sitting in a tent

warmed by the sun. If they go again, they won’t be out of the water before

1600, and then still in the tent, shaded and wind blown at 1700, with an

obligation to pack up and climb over to the summit camp as the mountain

makes its daily cycle from pleasant to formidably dangerous. I call the 2nd

dive is off, and radio to Randy our conditions. Now we have plenty of time to pack up

and return, and Nath sets up the Satellite phone for a call to the French

press before we go.

As soon as the diving was done, Pablo and Martin descended. They want to catch the other side of the

radio conversations between Randy and me. Randy trained the team, wrote the

protocols, and interpolated the high altitude diving tables for this

expedition only to be shut out from diving and even climbing with the team.

He is stuck at the refuge, waiting for reports on the progress

and conditions on the summit, pacing a trench in the floor.

Dive day 2

is a huge success. Every aspect planned and trained for inthe previous 6

months is achieved. The protocols are accurate, the physics work, the equipment is flawless, nobody dies. I feel a relief of pressure I didn’t even know I was carrying.

That night I have my best meal on the mountain,

“Lapin Chasseur con puree de pomes du terre et

champignons”. An initial look into the

foil pouch was not promising. Mostly

potato powder and chips of dried

rabbit here and there, but three minutes

later boiling water has turned it into a gourmet meal, which of course I get

on my mittens and recycled strainer turned balaclava while trying to eat it

before it turns cold. I can’t get it all out of the pouch, so I make a

secondserving of beef broth and croutons in the same pouch. I had hacked

outa big chunk of ice from under the snow pack, hopefully extremophile free,

and melted it for tea. Earl Grey this time, we are out of mint and I’m

tired of it any way.

Christian says, ‘Stop your weeping. You can

come back again next year’

The rest of the camp packes in to the tents. Clay and Rob

giggle while they download data on the computer. The

frat boys unusually quiet. I climb around

to the lee of the big rocks that make the lower

boundary of the camp and hide out from the wind, and

stay there through the sunset into

the starry night. Orion and his dogs rise upside down, in a

brilliance such that I can practically see the

change falling out of his belt purse, his dogs tail,

wagging.

There is no moon.

The meteors drill into the neighboring mountains

without slowing down.

I am alone in an extremeMars-Like environment, and I

am starting to thrive.

The End

RSS Feed

RSS Feed