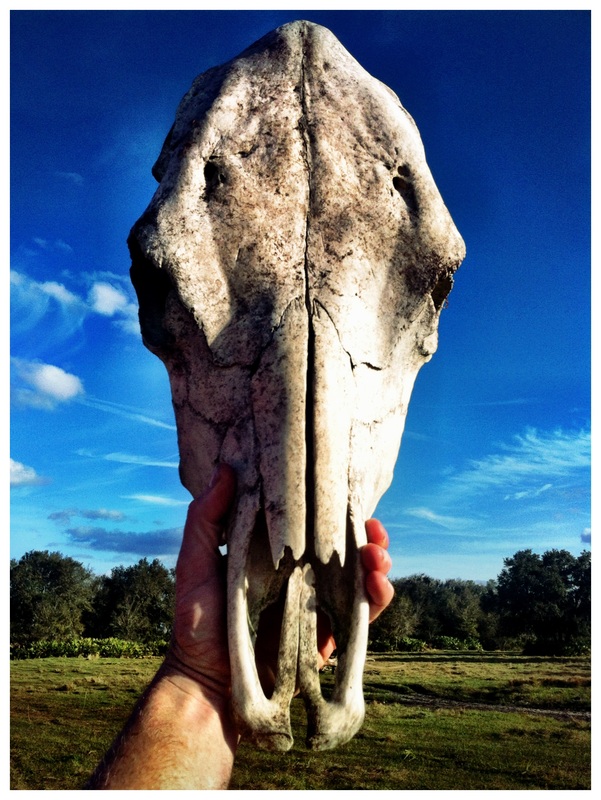

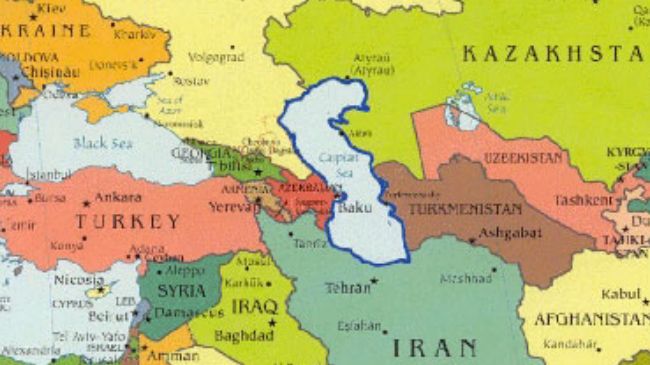

After 56 days on the Caspian Sea, Scientist Mike was still a pleasure to be around.

After 56 days on the Caspian Sea, Scientist Mike was still a pleasure to be around. Parkers concerned that a non-science major will keep him from being able to live a life he dreamed of, or worse, get him stuck in a life he wished to avoid.

I get it. As a young teen I was afraid that my own complacency might lead me settle into a suffocating mediocre existence. My response was to sabotaged my own future, making everything harder, figuring that if I was barred from the normal and never invited to the average, there would be little risk of me settling there. When my dad observed that I was burning my bridges in front of me, I responded " Ill cross those bridges when I'm too old to swim."

Clearly this is not career advice that I'd offer to any young person today, as it caused me a lot of extra work later on, but fortunately young ambitious people like Parker don't need to fear an average life if they bulk up their intangible skills and try to look at things with The Explorers Mindset.

Despite not having the right education or background, I've managed to make a career out of scientific exploration. Here's some bits of advice for young people that want to do the same:

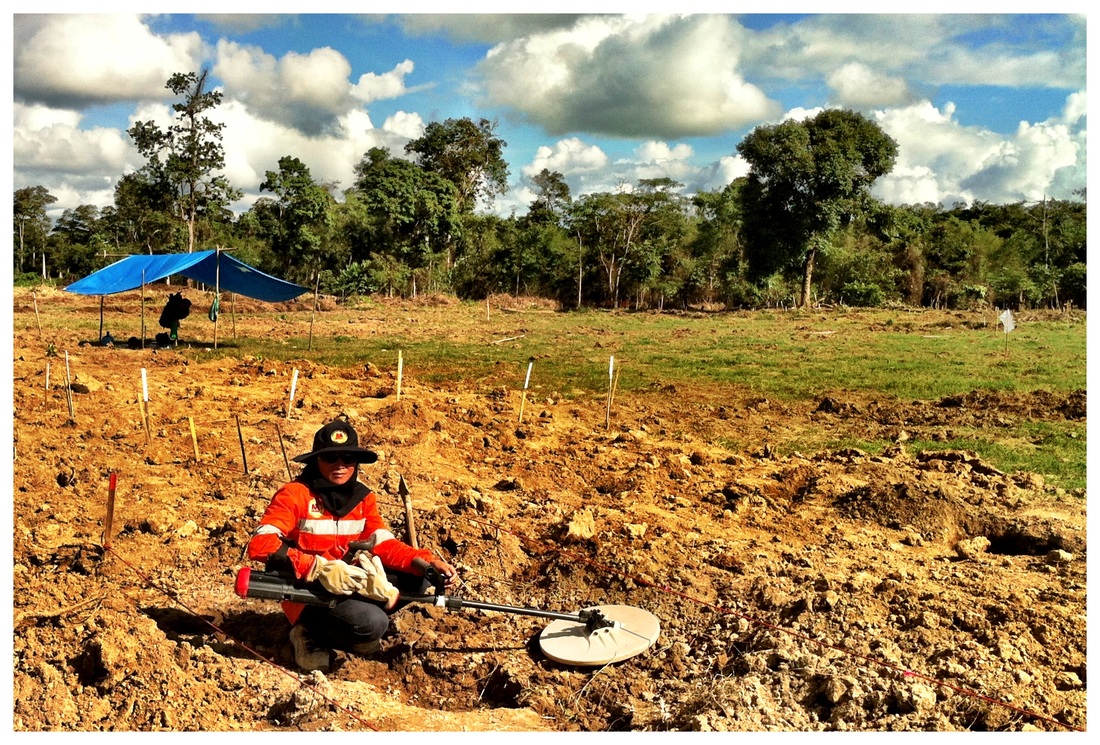

Every scientific expedition I've been on has been multi-disciplinary, with a little bit of overlapping skills, between participants. Many times important members of the team had no background in the specific area of study of the expedition, and yet were indispensable.

Some of the capabilities that seem to be most important for scientific field work are not ones that you learn in Classrooms. Example; being easy to get along with and happy about helping others out. Team players are way more important in the field than geniuses, especially when you are stuck together in a remote environment and need to rely on each other to get the mission accomplished. The hard to get along with are often left behind by the Expedition Leaders. Back at the lab at least people can escape selfish and unsupportive co-worker on nights and weekends.

Communication skills are paramount. "Exploration Means Publication", and the ability to contribute to scientific or academic papers is clear. But also the ability to communicate with the public in non scientific terms. Education and Public Outreach efforts are vey important to many expeditions, and that means blog posts, photography, and video story telling. Speaking foreign languages are great, but the ability to listen and understand.

What about general ability to fix things. Robot servo's aren't the only thing that break down and need fixing in the field. Fabricating out of equipment on hand

I watched Cristian Tambley build an underwater camera vehicle out of an old cot, and then successfully deploy it at 300 m depth.

The ability to do research is the ability to learn. and it applies to planning for a mission and trouble shooting as well as the science part.

The National Geographic institution has been around for a long time and the idea of seeking a job with them by sending an application to human resources seems very old school to me. But someone who has already let their passion for exploration take them out into the world is likely to have experiences and contacts that can make all kinds of goals come true. Asher Jay recently got named a National Geographic Emerging Explorer based on her passion and action for wildlife conservation, despite the fact that her background is in, of all things, fashion design.

I hope that this advice is useful, and if any readers want to expand the subject, please leave a comment below.

All the best,

Eric

RSS Feed

RSS Feed